Warning!

This website is under construction. Please keep all arms, legs and accessories inside the vehicle at all times.

In December 2015, I had the pleasure of being invited down into the bowels of the Crossrail tunnels, specifically the section between Stepney Green and Canary Wharf.

I also had my camera with me.

Hopefully the photographs I took emulate how impressive the trip was in real life...

Through the turnstile

The entrance to the above-ground complex at Stepney Green is fairly mundane, providing a rather unimpressive access into Europe's largest construction project.

The scale of the Crossrail project within, however, is colossal. The excavations that we were planning to explore today only form part of the wider C305 contract: named rather tersely as “Eastern Running Tunnels”.

This massive contract is the biggest design-bid-build construction contract of the whole project and includes three lengths of bored tunnel: Limmo Peninsula to Farringdon; Limmo Peninsula to Victoria Dock; Stepney Green to Pudding Mill Lane. It also includes launch shafts, launch adits (short sections of manually-dug tunnels where the tunnel boring machines begin their journeys from) and cross passages between the running tunnels, which can be up to 30 metres in length.

A view from the top

This image doesn't quite do justice to the scale of the Stepney Green shaft. It is truly spectacular, with stout concrete bracing beams casting shadows down onto the cavern floor and an inordinate volume of scaffolding walkways darting up and down, this way and that.

Beginning our descent

So... Down we went. I would suggest that descending this rattling staircase was not a task for the faint-hearted, with no evidence that it was attached to the shaft wall and plenty of wobbling to indicate the contrary. Even more fun for the acrophobic was the not insubstantial task of negotiating your way past people on their way up.

Still, the tight nature of the scaffolding stairs was a nice way to reexperience the awe of the shaft once we reached the bottom.

The labyrinth unfolds

Despite the scale of the shaft, once we reached the bottom it immediately felt cramped and over-busy. It wasn't hard to understand the logistical challenges associated with the regular hauling in and out of construction plant, not to mention the assembly, disassembly and removal of the massive tunnel boring machines (TBMs) at similar sites across the project.

Shafts of light

Once we had weaved our way through some of the infrastructure and facilities at the bottom of the shaft, suddenly the space opened out and the sky was revealed...

It was difficult to fit the whole of the shaft into one shot, and this image certainly doesn't do the depth or the size of the whole structure justice.

Each floor was a hive of activity. Goodness knows what was being constructed on the intermediate floors.

It's only temporary

There were several temporary props still in place that would eventually be sliced up and removed for scrap. Each must have been a good metre and a half across.

The first glimpse of a tunnel

At this point we came up against the widened entry to the tunnel.

Again, this shows how busy the interior of these subterranean creations can get. People were bustling about, MEWPs were whizzing back and forth and there was plenty of noise.

The caverns

Built to house the switch units splitting the central core into the Abbey Wood and Shenfield branches, each of the two Stepney Green caverns are amongst the largest using sprayed concrete lining ever constructed in Europe.

At 50m long, 17m wide and 14m high, the excavation of these monstrous spaces involved the removal of over 7500m³ of spoil, back up through those gaps in the roof.

Entering the tunnel

Beyond the caverns, each of the four bored tunnels disappears off on its own alignment... In our case, we intended to trudge up the westbound tunnel towards Canary Wharf and Abbey Wood beyond.

Here, you can see the interface between the manually excavated and shotcrete-lined tunnel, and the bored tunnel beyond.

Crossrail in all its finery

So this is it: the Crossrail tunnels in their purest form. Bored and simultaneously lined with preformed concrete units. Elegantly curved and graded. An engineering marvel under the streets of London.

A portal to the outside world

A brief look back to the door into the Stepney Green caverns and shaft.

Slab and duct

So, having been bored, lined and subsequently grouted, the tunnel we were walking through had also had the first layer of concrete slab poured in readiness for the more delicate track slab.

This image shows the means by which signalling and telecoms cabling will be fed through into the ducting cast within the slab... Rudimentary but effective!

On a slant

I have to say, it felt particularly exhilarating to be walking through these tunnels. There was something electric in the air (and I'm not talking about the buzz from the safety lighting), some sense of anticipation of the role the tunnels would fulfil once the whole system was up and running.

This shot perfectly shows how the first lay slab roughly matches the proposed cant alignment, which is then refined when the final track slab is laid later.

And the other way...

The track alignment through this section of the line is quite impressively curved as it dodges around the Limehouse Basin above.

In case you were wondering, the reason the cant is so pronounced through these tunnels is because there will only be one type of train running through them (in the vast majority of cases, at least).

This means that the cant alignment doesn't have to account for slower trains trundling through and damaging rails set at too low a cant deficiency, allowing cant to be optimised for the running characteristics of the Class 345 (the train that will operate all Crossrail services).

I am grout

Each of the precast concrete lining units has a grouting valve built into it, to allow concrete or another cementitious substance to be pumped into areas that the TBMs identified as being voided.

Once the TBM was clear of the tunnel and the lower slab had been laid, grouting teams came in and filled in these gaps. This image is a good example of a grouting site; the drips and scarring on the tunnel face will be cleaned up just prior to the handover of the tunnel to the railway fit-out contractors.

More curves

The alignment of the tunnels is really something.

The first cross-passage

This is the view of the first cross-passage we came upon (there are regular cross-passages to permit the safe movement of passengers from one tunnel to another in the case of an emergency).

Eventually these will be tidied up and, if all goes well, won't be seen again by the general public.

Sometimes, old is gold

Most of the cross-passages are lined in steel panels that would be equally familiar to a tunnelling engineer working on the London Underground extensions of the mid-twentieth century as to the current Crossrail workers.

Traffic lights

Given that the tunnel was largely complete (at least from the perspective of the C305 team), its main use was as a means of transit between other more active sites... At times of heightened activity, the tunnel apparently gets quite busy so this traffic light isn't so much a nice-to-have as a vital means of managing traffic flow.

Beep beep

Without the traffic light system, there would be a lot of reversing back and forth in the tunnel, seeing as there isn't really the room for vehicles to pass.

In any case, we were glad of the kerbs as this golf buggy whizzed past.

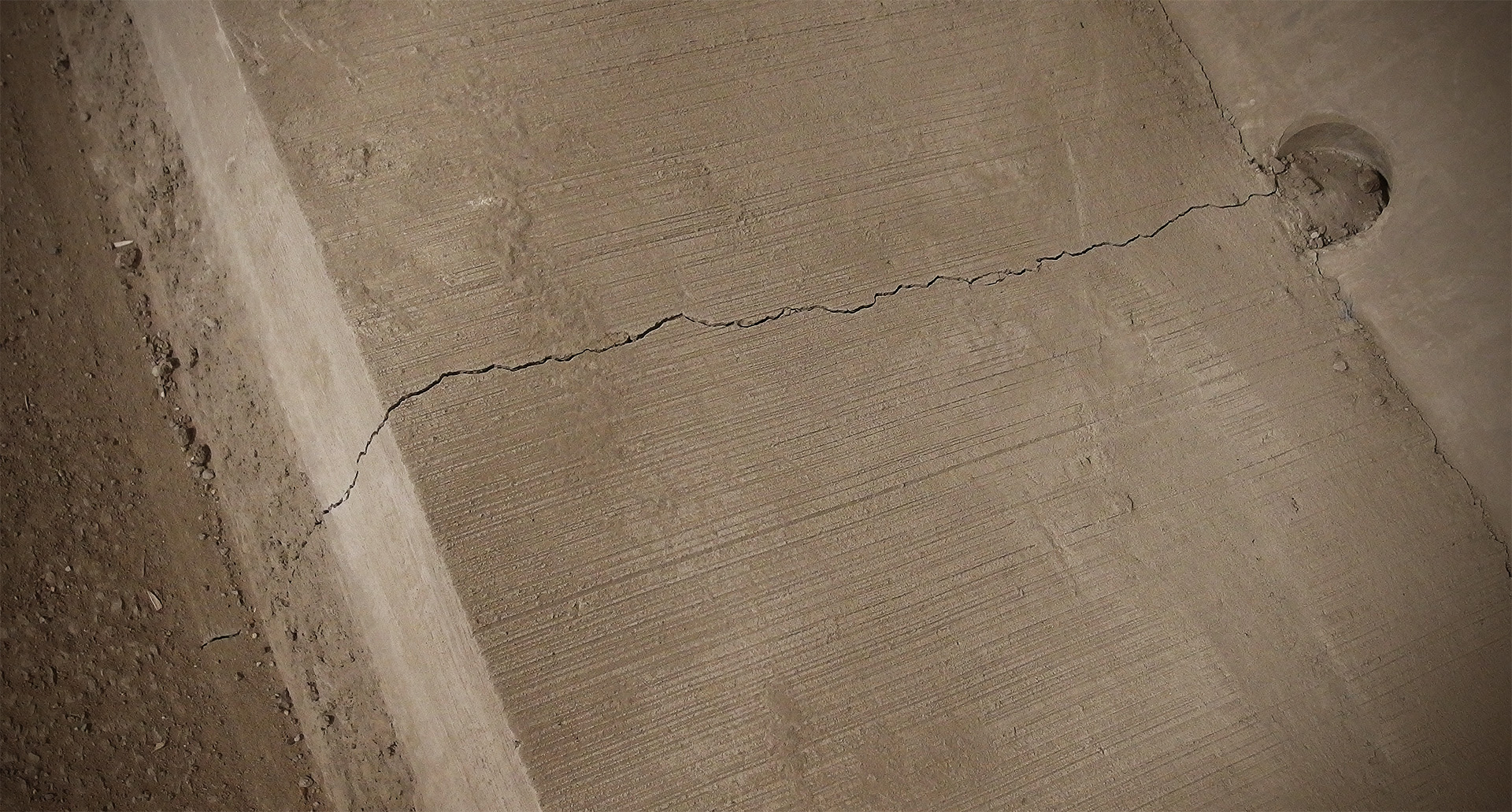

Mind the crack

For the uninitiated, this sort of damage might look a bit scary.

In actual fact, cracks such as these within the initial slab merit little attention. The mass concrete slab is more rigid than the surrounding tunnel lining (which is prone to an impressive amount of flex as the recently-bored ground around it settles).

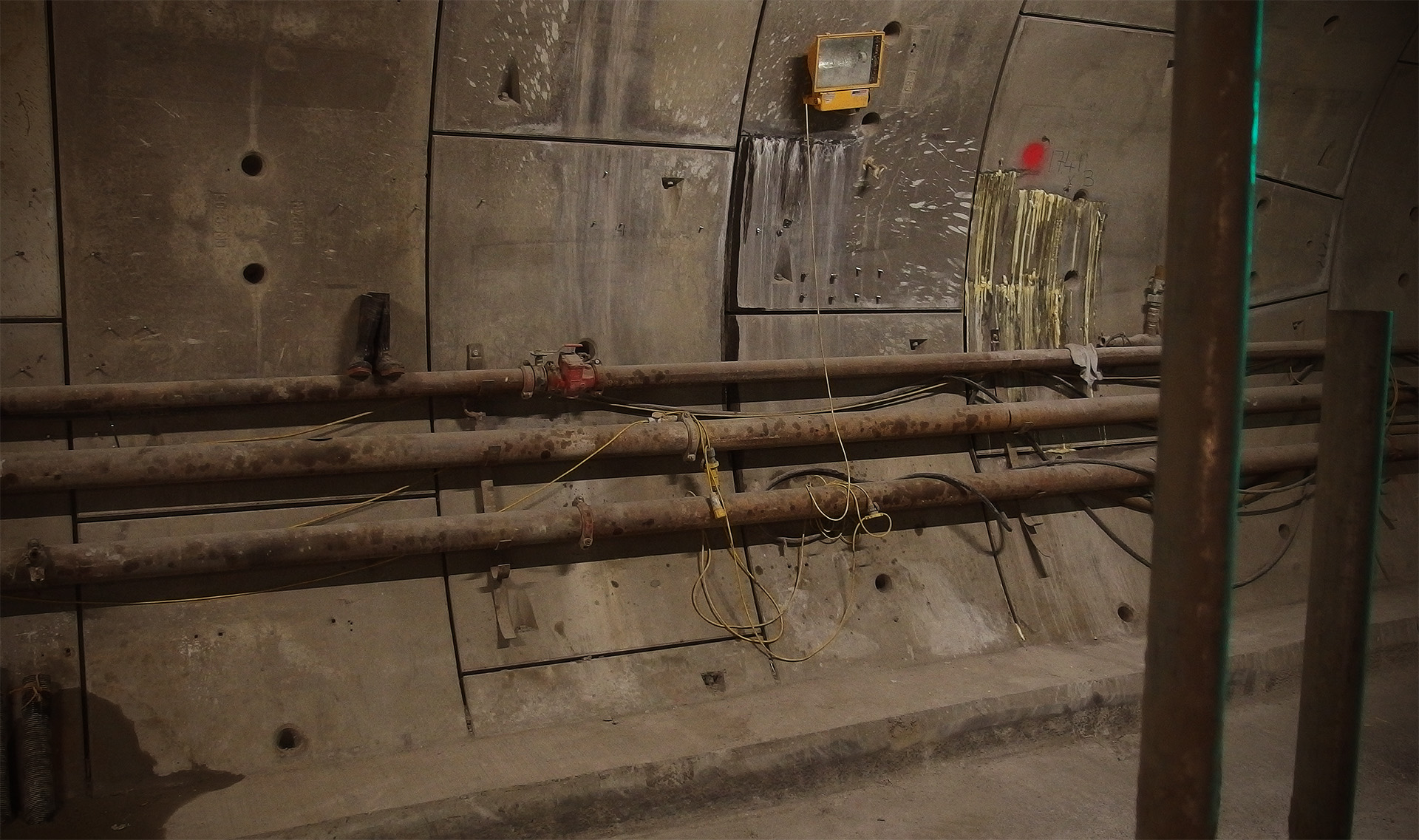

Deep tunnel drainage

The drainage system must be robust enough to cope with all manner of water ingress, and this surge chamber enables the accommodation of additional flows which are then pumped out manually when necessary.

Most of these are located within the cross-passages between running tunnels.

I particularly enjoyed the snakes and ladders arrangement here.

Lost and found

Wellingtons for sale, anyone?

The underground rollercoaster

Yet more curvaceous tunnelling, this time with an added bit of vertical geometry for good measure.

Crystal maze

These prism targets enable surveyors and engineers to monitor the position and alignment of the tunnels during and immediately after they are bored.

Straight up

The first of two shots up towards Canary Wharf station... This one really captures the natural rise used at stations to reduce energy consumption for braking and accelerating into stations.

...and again

A closer look towards Canary Wharf station, showing the difference in grade between station approach and the grade adjacent to the platform.

The train now arriving

So: Canary Wharf station.

No grade to grades here

A nice view back down into the tunnel, showing the vertical curve between the ascending tunnel grade and the level station grade.

Pre-prepared platforms

A rare view from the other side...

The platforms are 245 metres long, with the entire station sitting in a colossal 475-metre-long concrete box sunk into the West India North Dock.

At this point there isn't much to look at. The station development itself was entirely controlled by Canary Wharf Group, so there were large canvas hoardings protecting the architectural works from the dusty civil engineering.

Sneak preview

The canvas hoardings weren't quite enough to stop me sneaking a look in at the station, though there wasn't a great deal to see other than the glinting polished steel of the station interior.

The platform surface is still unlaid, with the final surface presumably to be laid as part of the railway systems fit-out contract.

Time to go

This shot is even better than the previous one at showing the vertical alignment coming into/out of the station. The gradient is pretty extreme and is further evidence of the opportunities presented by single-modal railway systems.

You raise me up

The grouting team were in action again once we returned through the tunnels to the Stepney Green caverns, with the man in the MEWP giving an idea of the scale of these subterranean shrines to shotcrete.

This is a view from inside the bored tunnel with our back to Canary Wharf station, and you can see the other bored tunnel in the background, snaking its way towards Whitechapel station and the rest of central London beyond.

Cavernous proportions

A view in the other direction, with the position of the previous shot having been in the mouth of the bored tunnel on the right.

The tunnel on the left disappears off towards Pudding Mill Lane portal and the surface route through Stratford towards Shenfield. Out to the section of Crossrail that I have worked on.

Again, the scale of the excavation is evident from the size of the operatives milling about within it.

One last look

A last look towards the tunnels that would invariably look very different the next time I passed through them.

This image shows how the cavern narrows as you go westwards, with the switch unit being contained almost entirely within it.

Reach for the sky

Alas, the sky beckons!

After what had felt like a good while traipsing through Subterranea Britannica, it was nice to see some sign of the natural world above.

Both the permanent concrete structures that will remain in-situ as well as the massive temporary steel props that will be removed when the shaft is closed out are visible here.

The photo still doesn't quite do the scale of the shaft structure justice.

Stairway to heaven

The rickety stairs to the outside world awaited.

I think this image shows the scale of the shaft better than the previous one.

The Crossrail Cat

Apparently, this feline intruder is a regular at the site, and seemed unfazed by the noisy, dusty chaos all around it.

Considering the length of time the C305 works had been going on, its no wonder the local prowlers had managed to find a way in and keep themselves entertained.

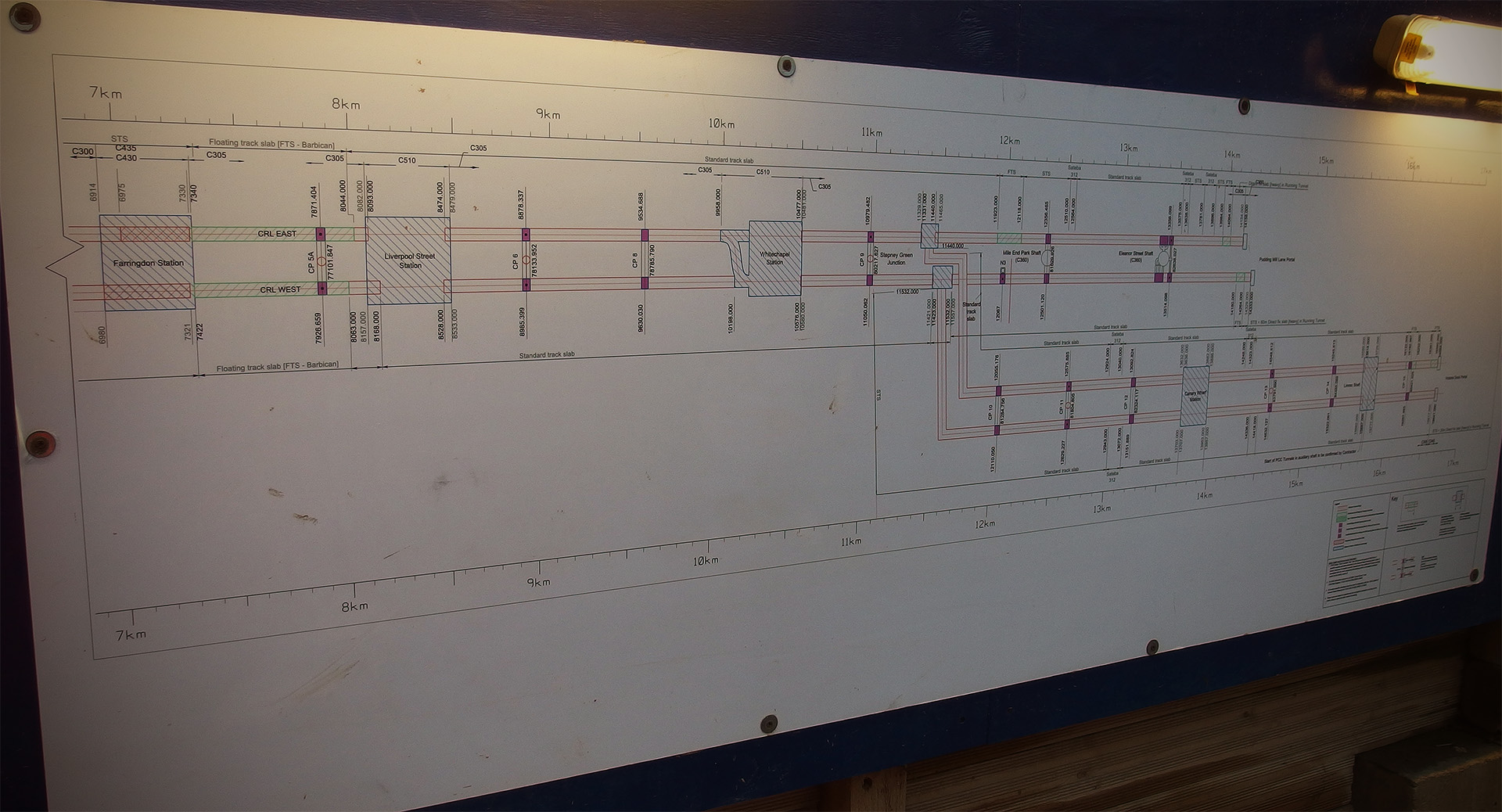

A schematic view

This drawing is a schematic view of the tunnels, including the position of cross-passages, shafts and stations.

Note the marked position of “floating track slab” underneath the Barbican and between Farringdon and Liverpool Street stations.

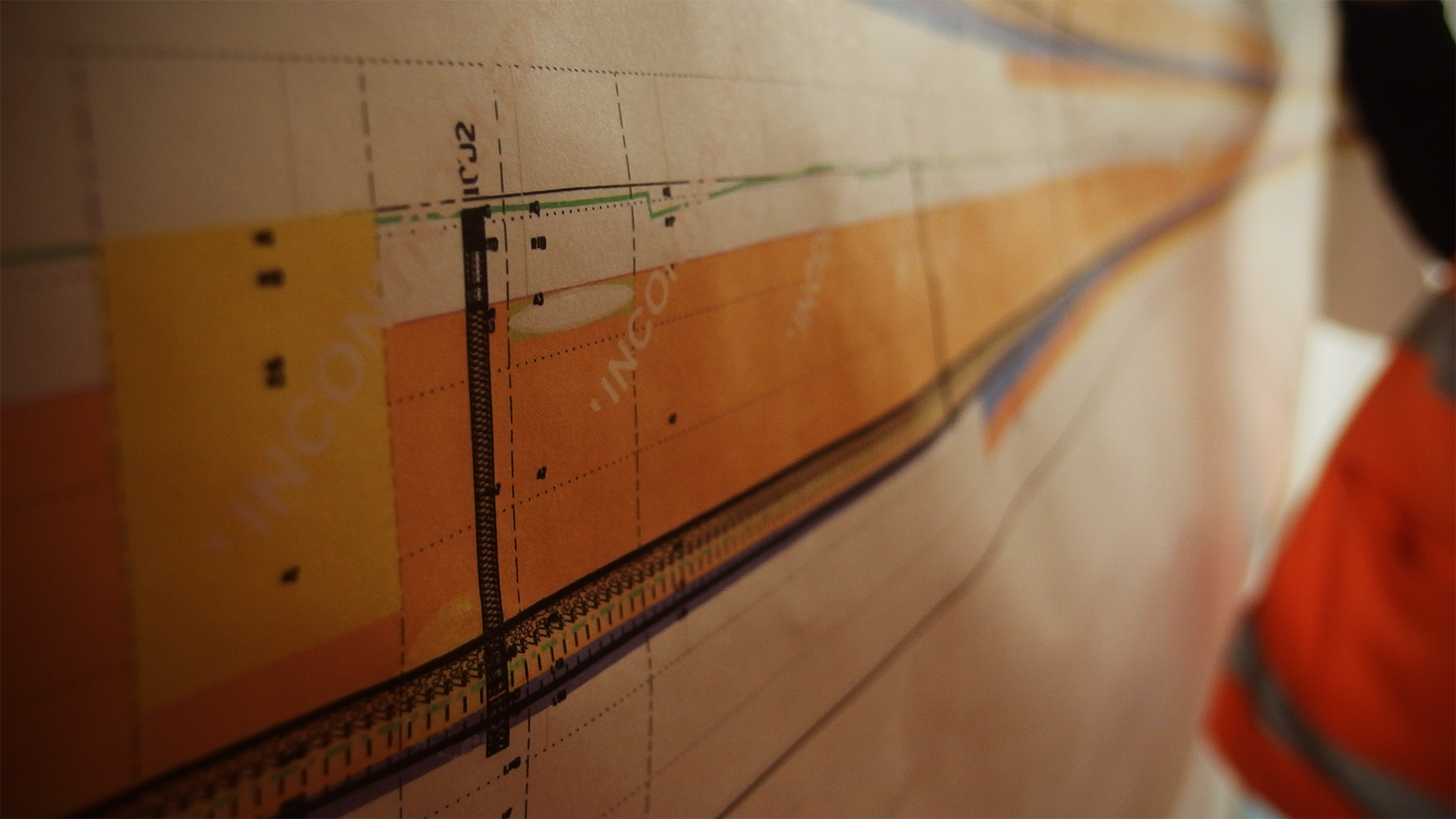

Horizontal and vertical

This map was pinned inside the site offices. Looking along its length gives an idea of the scale and the curviness of the Crossrail tunnels.

Having had a thorough look, it was time to remove the oranges and head back towards King's Cross for the train home.

What next?

Crossrail will be an exemplar for successful civil engineering megaprojects for a long while to come. Even if there are cost overruns or delays to the final opening, it will have led the way in terms of design, safety and overall engineering excellence.

It has captivated a generation of future engineers and is a success story for the railway industry and the wider engineering community.

I for one am very much looking forward to hopping on one of the new trains and whizzing purposelessly from Paddington to Abbey Wood station and back again.

Let's hope the precedent set by Crossrail is matched by future capacity-boosting UK rail projects.

Gareth is an engineer and writer, specialising in railway systems. As well as roles in design consultancy, he has written for several technical journals and for the railway press. He leads the York section of his professional institution, as well as being a lecturer in track systems at a newly-opened national engineering college.