Warning!

This website is under construction. Unattended luggage may be removed or destroyed by the security services.

A version of this article also appeared in Issue 844 (17 January 2018) of RAIL magazine.

Announced during the Chancellor's November budget statement, a new freight study is planned as part of the National Infrastructure Commission's first National Infrastructure Assessment. At the same time, there has been a lot of chatter about transferring more freight away from rail onto the road network.

Perhaps this has been instigated by the government's announcements about so called "platooning"; convoy running of HGVs. Maybe it's business magnate Elon Musk's unveiling of an electric HGV that he believes will spell "economic suicide" for the railway. Other more fanciful plans such as the overhead electrification of motorways have also been touted.

Former Secretary of State for Transport (and now former NIC chair) Lord Adonis has been particularly vocal on this front, recently tweeting:

Daytime freight trains take up huge amount of rail capacity & are a major cause of delays & disruption. Time to rethink freight logistics to get best use out of infrastructure, esp with lorry platooning likely soon. Major @NatInfraCom study just starting!

— Andrew Adonis (@Andrew_Adonis) November 25, 2017

As you'd expect, this prompted a keen reaction, not least from rail aficionados.

While a healthy discussion of the facts and the forming of policy based on evidence is only to be applauded, it's worth considering the key differences between the two modes of land-based freight transport.

The principle of load transfer

Rail (and rail freight in particular) owes its endurance to the fact that the engineering principles of the railway system permit a high level of control over the distribution of loads.

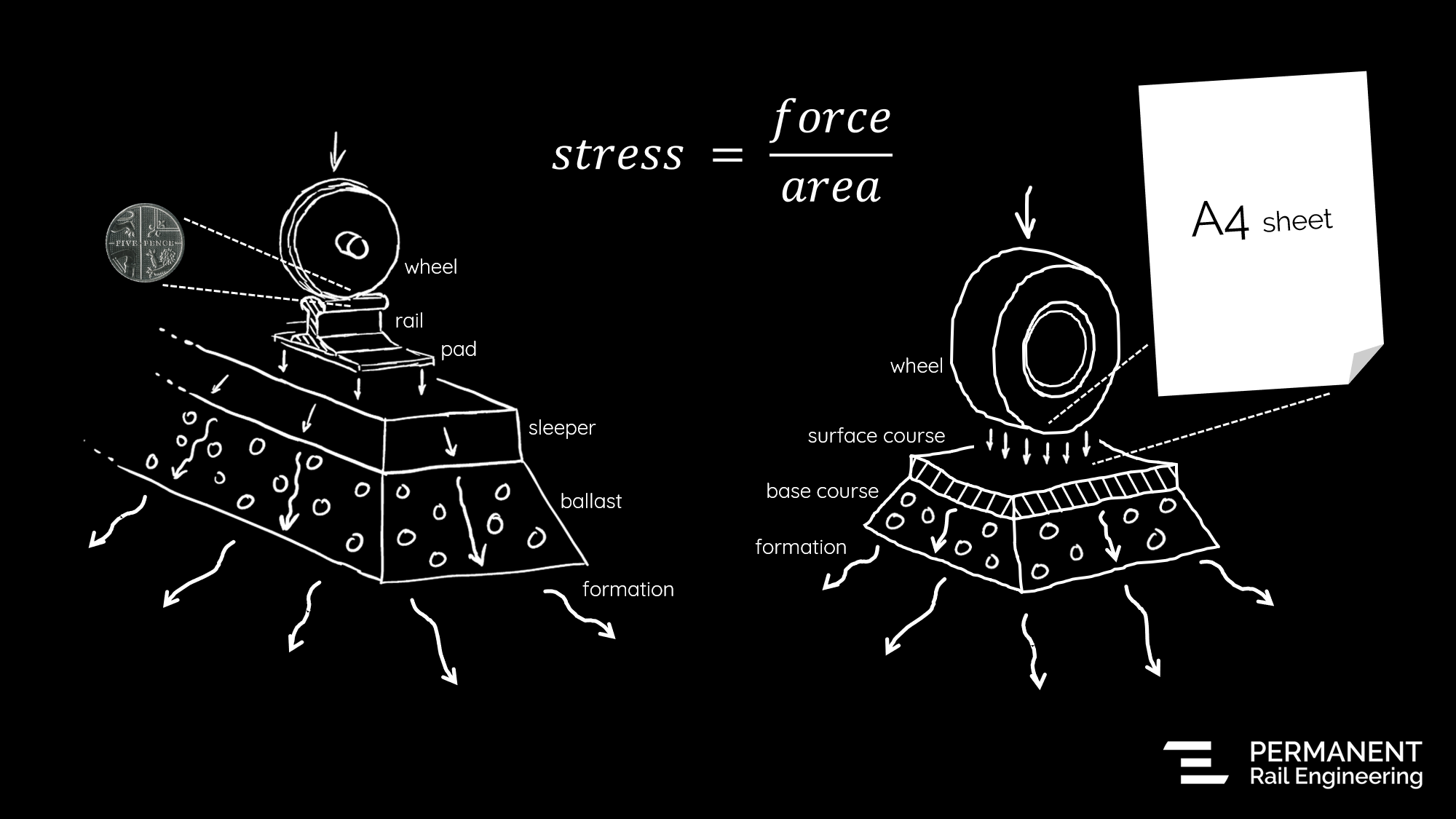

Stress (force divided by area) is transferred from the wheel into the rail, through the track (be it sleepers and ballast or slab-track), and down into the formation and supporting structures. This is known as "the principle of load transfer", and the ability to control each of these interfaces allows engineers to design a system that is unbeatably energy-efficient.

Arguably the most important of these interfaces is between the wheel and the rail. The principle of load transfer (combined with the strength of steel) permits the stress at the rail head to be very high, giving a contact patch under each wheel no larger than a five pence piece. Such a small area means friction is kept very low.

Highway design (while no less detailed) creates a system that is inherently more flexible. The majority of vertical load transfer under an HGV occurs at the interface between the pneumatic tyre and the tarmac. To reduce stresses, this contact patch is very large, resulting in much higher friction.

For every hundred miles that a train hauls one tonne, an HGV can only haul it thirty-five miles using the same amount of energy. This translates to a colossal advantage in terms of pulling power: one locomotive can haul the equivalent of up to 80 HGVs.

The flexibility of the highway surface has other downsides. The repeated passage of 40t axles over tarmac is like bouncing an orange on a bowl of old custard – it isn't long before the cracks start forming. That there is such a backlog of road surface repairs in the UK is no coincidence.

By 2019, the size of the road repair bill for local authorities alone will reach £14 billion, according to a recent report by the Local Government Association. While the maintenance of the railway's legacy infrastructure is also expensive, the equivalent costs for the road network are often overlooked.

The wider cost implications must therefore play a major role in the discussion, not least the true burden on the Exchequer of the maintenance (and enhancement) of our road and rail networks.

Elon Musk alleges that the running costs of a fleet of his Tesla HGVs are only 56% of those for rail, but has he included the costs to society of increased congestion (and the associated increase in road damage) resulting from a massive shift of freight onto our roads?

There are other factors at play that give rail freight a further advantage such as security and predictability. These are more circumstantial, however, and it isn't beyond the realms of possibility for an enlivened road haulage industry to overturn them. The negative impact on UK-wide carbon emissions of a transfer away from rail might also be offset by the uptake of electric vehicles and, conversely, by the current government's decision to curtail the roll-out of railway electrification.

The safety aspect

More critical than any of the physics or socio-economics is the safety of those on our roads.

In 2016, 273 people were killed in collisions involving HGVs. For the same period (and for the tenth year in a row), there were no passenger fatalities resulting from train accidents on the heavy rail network. If you look at accidents specifically caused by freight trains, the last fatality was at Stafford back in 1996.

The most important question that advocates of a shift of freight from rail to road must answer is this: how will they avoid the inevitable increase in fatalities resulting from putting more HGVs on the road?

Some may say that new technologies are capable of surmounting many or all of the issues detailed above. The rail industry should respond to this challenge with a unified voice, but the burden of proof must be on those such as Elon Musk advocating a great exodus of freight onto the road network.

Technologies may change but the defining principles of road and rail will not. The National Infrastructure Commission study must adequately account for this, if it is to effectively inform future transport policy.

Without truly seismic changes in HGV technology, rail's monopoly on the efficient transport of freight across land will continue to be unbroken.

Gareth is an engineer and writer, specialising in railway systems. As well as roles in design consultancy, he has written for several technical journals and for the railway press. He leads the York section of his professional institution, as well as being a lecturer in track systems at a newly-opened national engineering college.