Warning!

This website is under construction. If anything odd happens, blame someone else.

Following yet another sizeable fares hike for British rail passengers, there is a lot of chatter about how our railways are run and, more specifically, by whom.

The word on everyone's lips, away from official railway publicity at least, is nationalisation.

There are some very loud voices on the pro-nationalisation side of the argument, and some quieter but perhaps no less determined voices on the other. The trouble is, there seems to be a glut of aggravatory nonsense propagating from the pro-nationalisation crowd, and a belligerent suggestion that everything's fine from the pro-privatisationists (well, near enough).

Far too often I find myself (as a social democrat) rallying against the latest bit of cheap spin, including this ridiculous tweet suggesting that British trains offered lower safety standards:

Another big fare rise for rail travellers: 3.6%, the highest in 5 years. On overcrowded, ageing stock, with less staff & lower safety standards. Privatisation is the problem, not the answer. @UKLabour will bring rail franchises back into public ownership as they expire. #RailFail pic.twitter.com/jxSxEgQH5N

— Laura Pidcock MP (@LauraPidcockMP) January 2, 2018

This sort of thing is destroying the real discussion: that the subsidy of and investment in the railways (and other forms of public transport) isn’t great enough to allow fares to be reduced.

I'll set out my stall from the off: I'm a railway design engineer. I believe that the railways are a public service. I want rail travel to be practical, comfortable and competitively priced. I want the railway's market share of passenger and freight traffic to be much higher than it is now. I want investment to be consistent and measured fairly against its competitors.

There is one unassailable contradiction to this utopian state that the nationalisation argument completely fails to address:

FARES ARE TOO HIGH

For many people, the cost of rail travel is preventatively high. It's that simple.

Tickets are expensive enough that those who can afford it take the car and those who can't don't travel. As usual, the lowest earners are given a kicking.

This is a problem across all comparable countries, but in Britain it has become particularly acute since privatisation. Whilst comparisons with other countries are often poorly framed, it is certainly true that the complexity of our ticketing system usually prevents casual users from purchasing the cheapest fares.

As one excellent source of ticketing knowledge puts it, “Britain has the most commercially aggressive fares in Europe”. I’d argue that for many people, including new or disabled users, this usually results in exorbitant ticket prices.

People often favourably compare prices between rail and air, but if the railways are to be a force for social and environmental good, we should be comparing rail fares with the price of road travel instead.

IT ISN'T FEASIBLE TO DECREASE FARES

If fares were to suddenly decrease sharply overnight, it isn’t a great leap to say that the system couldn’t cope with the increase in passenger numbers.

Our railway is pretty full already, and a step-change in capacity is at least a decade away... Suffice to say that significant jumps in passenger numbers would result in a major drop in reliability and a hefty hike in running costs.

Fares are also horrendously complex. There is no single baddie responsible for this: the fares system has retained parts from pre-nationalisation days, it wasn’t radically improved by British Rail and its structure was mostly cryogenically frozen following privatisation.

An across-the-board fares reduction would be incredibly hard to implement fairly (independent of who was running the trains) without a complete overhaul of the ticketing system, and we all know how massive government-specified IT projects (with frightening time pressure and an undefined scope) usually go...

Without a major change though, this situation won't improve. Little tweaks of who owns what train operator will not make a shred of difference.

Accepting these two ugly and opposing truths, what is there to be done?

In the spirit of the subject matter, let's try and break things down into manageable chunks:

The modern railway is a tremendous success

Independently of who is running what, and indeed how fragmented our current railway system is, it has been a tremendous success since the turn of the millennium.

Perhaps spurred on by early failures (some of them tragic), the railway under its current part-privatised, part-nationalised regime is going from strength to strength:

- • greatly increased passenger numbers

- • immensely improved safety

- • massive infrastructure investment

- • huge numbers of new rolling stock

- • an ever-increasing volume of railway research

This is in no small part down to the passion and expertise of thousands of dedicated rail staff across the country, who would be planning, installing, maintaining and operating the railway system with the same zeal no matter who was running the show.

Privatisation was a horrific mess

The subject of how bad a job John Major's government did at privatising British Rail deserves (and receives) volumes of analysis.

It's difficult to find an informed voice across the political spectrum who can confidently say that the Railways Act 1993 was a perfect piece of legislation. Even the (currently Conservative) Department for Transport admitted this in their recent strategy paper.

Perhaps the most criminal aspect of the whole thing was the transfer of physical assets (infrastructure and rolling stock) to the privateers at an eye-watering net loss to the public purse... As with the recent privatisation of Royal Mail, those who priced the assets for sale also seemed to end up being the ones who profited from them being so "cheap".

For New Labour, who are often lumped with some of the blame for not reversing the process once they gained power in 1997, this fire sale of hard-won public assets was so grossly biased in favour of the buyers (and wrapped in legal complexities) that nicking everything back again would have been a frighteningly expensive nightmare.

We may have been having a very different conversation but for a cruel twist of fate in the sudden death of a Conservative advocate of a more rational approach to privatisation. In any case, Major’s government pressed ahead with the near-total disintegration of British Rail.

The railway system is already (mostly) nationalised

It might seem strange that, following this aggressive push to shift the railway into the private sector, the DfT then took more control of the system than it had ever had before.

Now that the newly-privatised railways consisted of so many scattered pieces, Whitehall found itself having to tell everyone what everyone else was doing. In true Thatcherite style, giving up public ownership meant a massive power-grab by central government.

Today, the mandarins specify how franchises are run, the cost of many fares (including season tickets), the design of many new trains, where infrastructure investment is directed, the shape of the timetable, and much more.

To top off this ideological paradox, in 2014 the Conservative-led coalition actually re-nationalised the railways (in the literal sense) by bringing Network Rail (owner and maintainer of most fixed assets) back into full public ownership.

Nationalisation is no panacea

The net result of all this is that today's government gets to meddle more in the workings of the railway than ever occurred under the nationalised British Rail.

It's not unreasonable, therefore, to suggest that most of the problems on the railway are the government's fault in the first place.

Certainly, the fares system is regulated heavily by the DfT... Government is indeed directly responsible for half of fare increases. The percentage of public subsidy versus fare revenue that funds the network is also government controlled.

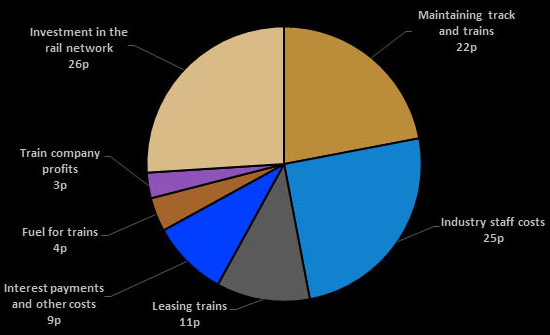

The 3-4% profit and the management bonuses of the TOCs (generally referred to as dividend leakage) doesn't really represent that much in the grand scheme of things. Sacking all the staff at the interface between Network Rail and the TOCs (particularly the legal and commercial roles) might save a bit more dosh, but this isn't what is being proposed by Labour, and I daresay it wouldn't go down that well anyway.

When it comes to the cost to passengers, therefore, it is difficult to see how the changes proposed by Labour’s nationalisation will result in noticeable savings. No matter what the size of the windfall, it would only happen once.

What exactly is nationalisation?

In the first 2018 issue of Rail Magazine, Labour’s rail policy advisor talked a lot about fragmentation of the industry (arguably the biggest issue with the current system) but didn’t say much about the actual plans to resolve this.

What Labour seemingly mean by nationalisation is a return of the current franchise operators to full public ownership à la the operation of intercity services on the East Coast Main Line from 2009-2015. It also isn’t clear if this would be a single national operator or a devolved set of operators broadly in line with current franchise boundaries.

They don’t appear to have mentioned (a) the open access operators (Eurostar, Hull Trains or Grand Central, for example), (b) buying back billions of pounds worth of rolling stock or (c) the hundreds of companies (in consultancy, manufacturing, technology, etc.) that dropped out of British Rail in the run up to full privatisation.

In the latter case this is quite sensible (those companies are long gone and the world has moved on), but Labour’s plans would hardly merit celebration as a socialist revolution if most rolling stock remains under the ownership of the banks.

On the flipside, this means that the dramatic sounding "nationalisation" of the railway really involves quite a minor tweak to the existing system.

Why, then, are the anti-nationalisers in such a panic?

Franchising is hugely unpopular and has few merits

The fear being stoked by the current discussion might be thus:

- • a nationalised railway, whatever that might be, is a hugely popular idea right now; and

- • with the current government committing hari-kari over the most spectacular act of economic, political and social vandalism in modern history, there’s a pretty strong likelihood that Labour get into power and make “nationalisation” happen.

Polling shows that the public at large quite like the idea of “nationalisation”. Perhaps more scientifically, Transport Focus regularly demonstrate that passengers don’t care who runs their trains so long as they don’t cost too much, aren’t overcrowded and are frequent enough to be useful.

Despite this, the official railway bodies (like the Rail Delivery Group) are totally silent. Not a peep in defence of a genuinely successful railway network. Is it because they feel that their demise might be an inevitability and they don’t wish to upset their future masters?

Your guess is as good as mine.

In terms of the success of the franchised railway network, people often point to greatly increased passenger numbers and overall satisfaction, but this is probably correlative rather than causative. For now, at least, we are still richer than we were in the 1980s.

Advocates of the current setup also suggest that a for-profit railway with franchises in competition with each other is good for service provision and quality.

It is certain that the railways are smoother, slicker and safer than they have ever been (I am quite content with the use of the phrase “railway renaissance”), but does the little sliver of profit that keeps being mentioned make that much difference? Investment in the railways has gone up since privatisation, but it is essentially all public money anyway.

One thing must be certain: there is no such thing as competition in such a complex and closed system as a railway network.

The problem with franchising is that government is asking the market to tell it how to run the network with one hand, and controlling the variables that determine how the network will run on the other.

In the concession model, government accepts that it controls many of the variables and simply tells bidders which parameters it expects them to run the system under and for what return.

Having already been put to good use by Transport for London, the concession model is being proposed in favour of franchising in several cases by the DfT itself, proving that the life of the franchise model is nearly up whoever you vote for.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how the system is run, so long as the expertise to run it is in place, and the industry is given enough space to plan far into the future.

Personally, I believe that vertical integration would do a better job at providing this than all the little bits and pieces that exist now, but this isn’t necessarily nationalisation and it still won’t solve the railway’s many problems. It certainly won’t reduce fares.

Government cannot de-fund the railways as in previous decades

It is a very legitimate fear of the non-ideologically driven anti-nationalisers that giving back full control to government risks (or even guarantees) a return to the dirty days of a minimally-funded railway system desperately limping from year to year.

This will never again be the case.

Firstly, the world has changed, and railways are now too critical a component of the economic functions of the country to be left to rot as in years gone by.

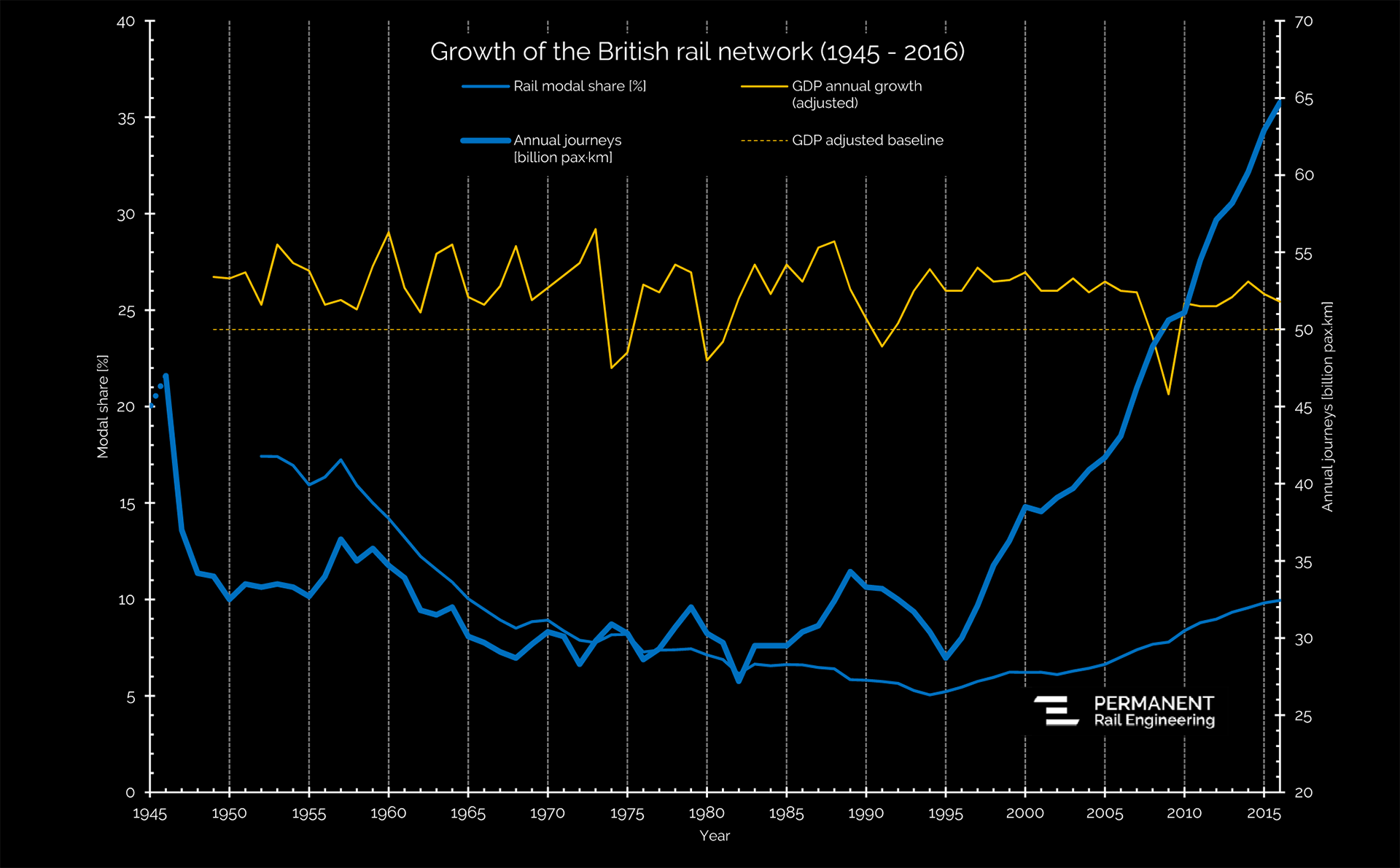

Today’s number of passengers is over 240% greater than those of the low point in 1982. In fact, if you put GDP next to passenger numbers, you can see that the impact of the 2008 financial crisis (which was deeper than the previous three major recessions) barely knocked rail usage at all...

Freight, too, relies on the railway in ways that would put a smile on the faces of the old Victorian engineers who built them in the first place. The growth of intermodal transport on rail is a massive success story.

A graph showing the growth of the British rail network from 1945 to 2016

The shape of society and the way it moves about has changed for good, and both of the main parties know this. To survive, a government must sound like it supports the railway, and it isn’t easy to do this without putting their money where their mouth is.

Secondly, the railway budget is already controlled, and regularly manipulated for the worse, by government. The DfT still makes hugely stupid, short-termist decisions about investment. It's just that today, these impact even more on the micro-management of the system rather than on the headline budget (see: electrification, IEPs, digital railway).

Surely relinquishing Whitehall’s grip on the railway by reducing its fragmentation might improve the situation slightly?

Whilst I have that graph up, notice that just prior to each of the recessions (1973-75 and the early 80s/90s), passenger numbers had started to tentatively climb. The early 90s recession was a particularly deep one and this greatly stymied the growth that British Rail had been continuing to foster through the roll-out of new rolling stock, electrification and sectorisation.

Despite having very little money to spend and getting kicked about like an old tin can, British Rail did do rather well.

It all comes down to expenditure

The only way to decrease the cost of rail travel is to increase the percentage of the overall rail budget that is funded by the taxpayer. This would be true no matter who owns its constituent parts.

Even then, the whole network would fall over from being over-used. In order to reduce fares you need to increase capacity, and this means more railway investment in projects like High Speed Two and High Speed Three (whatever that might entail – more on this sort of thing elsewhere) to reduce the difference between train speeds on individual lines and thus increase overall system capacity.

So, increased subsidies and increased investment are the only answer to the fares question.

The trouble is, transport (up-turned hat outstretched) must line up next to welfare, and behind health and education, in the queue for taxpayers' cash. The discussion then becomes one of the greater expenditure of government as a whole, and not one to have here.

At which point, the nationalisation argument becomes trivial. It is a political, not a practical one. It's easy to support loudly and it means very little in reality.

As a socialist, I'd much rather the Labour party shifted its rhetoric towards increasing public transport investment and, once the fully integrated system (bus, tram, cycle, etc.) can pick up the slack, removing the shadow subsidies for private travel.

Only then could extortionate fares start to come down.

Disagree?

Let me know why... The best place to do this is Twitter, but I'll respond to emails too! The most interesting comments will be added below.

Gareth is an engineer and writer, specialising in railway systems. As well as roles in design consultancy, he has written for several technical journals and for the railway press. He leads the York section of his professional institution, as well as being a lecturer in track systems at a newly-opened national engineering college.